As modern vehicles, and even more so electric vehicles, become increasingly connected, their vulnerability to cyber attacks continues to grow. Gaël Musquet, ethical hacker and cybersecurity specialist, warns of the vulnerabilities of these connected systems from the Campus Cyber in the heart of the La Défense district, a place that brings together many cybersecurity players. And for him, no technology is infallible. His watchword? Resilience. Interview.

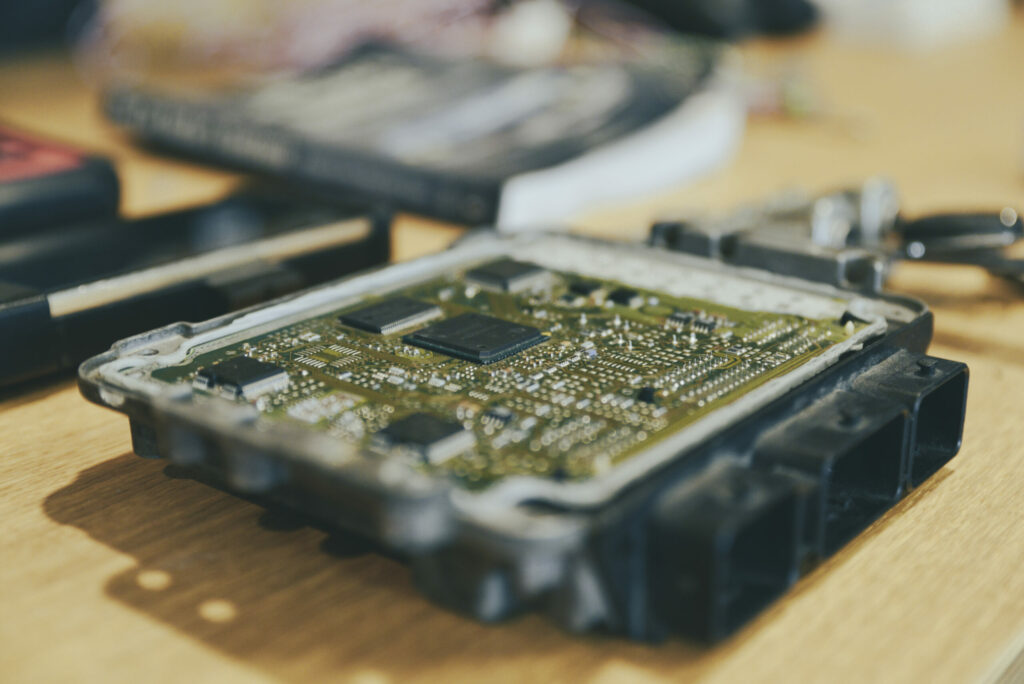

A windy afternoon in the La Défense district. Gaël Musquet, a meteorologist by training, ethical hacker and Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Mérite, welcomes us to his HQ, the Campus Cyber, a « totem pole » bringing together hundreds of companies dedicated to cybersecurity. He takes us on a tour with what he familiarly calls his « toys » in his arms: drones, a whole bunch of cables, screens and printed circuits that he uses and/or makes in his lab. His current project? A rover that can be remotely piloted and used in military operations.

But Gaël Musquet’s biggest toy is his car. A Toyota C-HR hybrid that, from the outside, looks no different from the production model. Named ‘Red Pearl’ (in reference to the colour of the livery and the Caribbean origins of its owner, who is technically… a pirate of the Caribbean), it is a ‘show car’ hacked by Musquet himself, which he dismantles and hacks in public at conferences and which, at the touch of a button on the cruise control, transforms itself into an autonomous vehicle, with the exception of detecting tolls and a few problems with roundabouts.

After taking ECO MOTORS NEWS on board for a demonstration of the almost limitless possibilities of car hacking – the car detects blind spots better and manages its braking better than the person writing these lines, to be honest – the ethical hacker took the time to sit down for a few minutes with us, for an interview.

What do you think are the main cyber risks facing electric cars today?

Gaël Musquet: Electric vehicles present five major attack surfaces. The first is physical: opening, theft of the vehicle, access to the passenger compartment, etc. The second is radioelectric: for example, NFC badges or contactless keys are targets. The second is radio: for example, NFC badges or contactless keys are targets. Then there are electronic vulnerabilities, via on-board data buses. Once physical or radio access has been compromised, action can be taken via these interfaces. The last two concern software installed on ECUs and on-board computers and data produced or received by the vehicle, such as connections to websites or manufacturer services. These are all entry points for cybercriminals.

You’ve hacked into your own car, which you use as a show car for your business. Can you tell us about it?

Gaël Musquet: I wanted to show these vulnerabilities in a concrete way. It’s important not to get bogged down in rhetoric or abstract standards. We’re talking about 140,000 car thefts in 2024 in France, that’s one every four minutes! So I’ve created a ‘show car’ which, as well as being autonomous, is above all a guinea pig that I can take apart, test and show. I use it to illustrate real issues and to advise customers and partners.

And it’s all available as open source…

G.M. : Absolutely. My vehicle is based on open source software and hardware. The idea is that everything I demonstrate should be reproducible. Open source software allows the code to be collectively audited, which strengthens security. And it also guarantees a degree of technological sovereignty, since it is not dependent on a private player or a foreign state.

In your work on critical infrastructures, you often talk about resilience. How vulnerable is the recharging network to cyber attacks?

G.M. : No system is invulnerable. The real question is: how long will it take an attacker to bring it down? To build a resilient network, we need diversity in technical solutions and a culture of audit: penetration tests, code reviews, contributions from open source communities (such as the Linux foundation or the EVerest project). Some countries, such as Japan, are already opting for this openness, which makes their systems more resilient.

Is there a need for an « audit culture » in the automotive sector, as there is in the banking and energy sectors?

G.M. : Yes, it’s essential. For the past two years, manufacturers have been required to incorporate cyber security into vehicle design. But this is still not enough. We need to give hackers access to vehicles so that they can audit them and organise bug bounties, rewarding those who find flaws. And above all, we need to think about cyber maintenance: developing standards, processes, updates, etc. We need cybersecurity crash tests, just as we do for physical security.

With the advent of bi-directional charging (V2G), cars can inject energy into the network. Is this a new entry point for cyber threats?

G.M. : Yes, clearly. It’s no longer just an exchange of fuel, but an exchange of data and energy. It also involves new players: energy suppliers, payment operators, network managers. The stability of the entire electricity network is at stake.

As consumers, what can we do to protect ourselves from these attacks?

G.M. : There are a few simple things you can do: lock your vehicle and, when you get home, keep your keys away from your door and windows, especially if they are contactless; apply software updates to your vehicle, as you would to your smartphone; and protect access to your vehicle by parking it in supervised areas, or by using mechanical anti-theft devices such as the steering wheel lock. These measures may seem anachronistic, but they are still effective in delaying or deterring an attacker.

Are you optimistic about the development of automotive cyber security?

G.M. : Yes, very much so. At Campus Cyber, I see an active ecosystem, exchanges between peers, but also with passionate young people. In fact, I’m taking on eight of them on work placements this month! The automotive industry needs to be promoted among young people. The technical professions (mechanics, electrical engineers, etc.) are noble and essential to electromobility. It’s up to us to pass on this passion. There are 60,000 vacancies in the cyber sector today, and they will be essential tomorrow.

You often talk about « getting your hands dirty ». Is this an important part of your approach?

G.M.: Absolutely. The manual side of things is sometimes devalued, but we need people who touch, test and manufacture, whether it’s hardware or code. My job is 80% human and 20% technical. Understanding fears, needs and emotions is what enables us to create effective solutions. Technology alone is not enough if we don’t know how to explain, support and create meaning.